Collaborative Github Workflow

From eqqon

m (→Getting Started) |

m (→An Alternative for Github's Network Graph) |

||

| (34 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

__NOTOC__ | __NOTOC__ | ||

==== ==== | ==== ==== | ||

| - | <div style="float:right;width: | + | <div style="float:right;width:400px;margin:30px;border:solid1px;"> |

[[Image:Distributed repository structure on github.png|right]]<br> | [[Image:Distributed repository structure on github.png|right]]<br> | ||

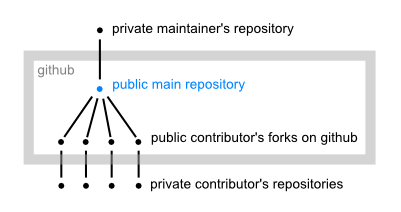

Typical distributed setup of git repositories for collaboration on a github hosted project. The dots are repositories, the lines between them indicate that one repository has been cloned from another. The forks are initially created by cloning from the main repository and the private repos are clones from the public ones on github. | Typical distributed setup of git repositories for collaboration on a github hosted project. The dots are repositories, the lines between them indicate that one repository has been cloned from another. The forks are initially created by cloning from the main repository and the private repos are clones from the public ones on github. | ||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

== The example == | == The example == | ||

| - | This description uses the project [[GitSharp]] | + | This description uses the project [[GitSharp]] as example. Git# is the CSharp implementation for Windows and Mono. |

The '''main repository''' also called the '''upstream branch''' is [http://github.com/henon/GitSharp/tree/master henon/GitSharp]. The '''maintainers''' of this repository are responsible of merging in contributor's commits. | The '''main repository''' also called the '''upstream branch''' is [http://github.com/henon/GitSharp/tree/master henon/GitSharp]. The '''maintainers''' of this repository are responsible of merging in contributor's commits. | ||

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

== Contributor's Workflow == | == Contributor's Workflow == | ||

=== Getting Started === | === Getting Started === | ||

| - | ; | + | <br> |

| + | ;Overview: | ||

* Fork | * Fork | ||

* Install tools like git itself (if not yet done) | * Install tools like git itself (if not yet done) | ||

* Clone | * Clone | ||

* Start coding ;) | * Start coding ;) | ||

| - | + | * Commit early and commit often | |

| + | * Ignore the Github Fork Queue | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

;Fork: | ;Fork: | ||

| - | Say you want to '''start contributing''' to a project on github. The first thing to do is to fork it on github. Forking is the preferred way of collaboration on github and it works quite well with git. Just follow the instructions on github. Now you should have your own public repository which contains exactly the same history as the main repository at the time you forked. You will later push your contributions into this repository and the maintainers of the main repository will pull your commits into the main branch. | + | Say you want to '''start contributing''' to a project on github. The first thing to do is to fork it on github. Forking is the preferred way of collaboration on github and it works quite well with git. Just follow the [http://github.com/guides/home instructions] on github. Now you should have your own public repository which contains exactly the same history as the main repository at the time you forked. You will later push your contributions into this repository and the maintainers of the main repository will pull your commits into the main branch. |

| + | |||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | ;Install Git Tools (Windows): | ||

| + | * msysgit: make sure it is configured to use OpenSSH and that automatic line ending conversion is turned off during installation. You can use the msysgit-bash to use git from the command line. | ||

| + | * TortoiseGit: is not yet completely done but is already very usable for things like adding files, committing changes or resolving merge conflicts. | ||

| + | If you prefer other tools let me know what they are especially good for. I will include them in this document. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | ;Clone: | ||

| + | By cloning your fork on github you create your private local repository on your box. You will mostly work with it and only publish changes to github when you feel they should be merged into the main repository. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{code|git clone git@github.com:YOURNAME/GitSharp.git}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Of course this only works if you managed to create an SSH key and successfully uploaded it to github. I will not go into details on this, because it is already documented very well on github itself. If you experienced any problems with this step tell me and I will put them here. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Now you got a git repository called GitSharp and are ready to start coding! | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | ;Start Coding!: | ||

| + | Coding with git backing you up is really cool because you can so easily work on multiple topics at the same time efficiently. I'll give you a simple example: | ||

| + | |||

| + | You got a cool new idea and start working on it. You modify some files. You are not yet done, and your changes not even compile yet. Meanwhile you read on the mailing list that someone has got a problem with a specific test case and cannot get it to work. You would like to help because you know things like these very well and you are the type of human who cannot resist doing good :D. But what to do with your non finished code? Stash it away! | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{code|git stash topic_XY}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Git saves away your changes and your working copy is clean and compiles again. Now you fix the bug for your friend, commit the fix and publish it to your fork where others can access it. We talk about publishing contributions later more thoroughly. | ||

| + | Now you can apply your saved away changes and continue working on it: | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{code|git stash apply topic_XY}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | This is only a small example of how git supports non-linear development in a great way. Read more on it in the docs linked under '''Further Reading'''. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | ;Commit Early and Commit Often | ||

| + | When you are doing much coding, maybe refactoring a large code base or commenting source code you should keep in mind that other's are also modifying the same code base and that conflicts may arise. In order to make it easier for you and the others to resolve such conflicts on a per-commit basis try to commit as often as possible and commit only small changes. Provide a meaningful message for every commit so that anyone reviewing the commit later knows from reading the message what the commit changes. | ||

| + | |||

| + | For the beginner I'd suggest seperating unrelated changes on a file per file basis, although git allows much more fine-grained control over the changes to commit. Committing a selection of files can most conveniently be done in TortoiseGit. You can select the files that you want to commit, compare against the local repository what changes you made and comment your changes in the commit message. Of course it can also be done on the command line interface First stage all changes you want to commit by using git add. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{code|git add FILE1 [FILE2] ...}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | If you don't want to stage all changes in a file but only certain hunks, use the interactive mode | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{code|git add -i}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Now check if everything has been added or if you missed something | ||

| + | {{code|git status}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Committing on the command line (btw, never forget -a): | ||

| + | {{code|git commit -a -m"The commit message"}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Always keep in mind that errors happen all the time. If it is later necessary to revert certain changes because they broke something else's code then reverting a small commit is easy and not much of a problem. If the change to be reverted is mixed up with lots of other changes the reverting of such a commit will be a painful night mare. If you have already committed a "monster commit" to your local repo then don't worry. With git it is no problem to rewrite the commit history. Read about that later. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Here are some examples of commit messages for some unrelated changes that should not be committed in the same commit object would be: | ||

| + | * Converted all line endings to CRLF in the complete code base | ||

| + | * Documented the methods of Class XY | ||

| + | * Fixed TestcaseXY so that it now passes | ||

| + | * Added a new Feature to the UI, description follows: ... | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | ;Ignore the Github Fork Queue: | ||

| + | It's evil! The fork queue is a tool for maintainers who like to pick single commits from contributors but don't wish to merge in their whole branch. If you play around with the fork queue you will corrupt your fork (it can be fixed though, read '''Something went wrong'''). Many newbies on github feel like they should do something with the fork queue because there are a lot of possibly conflicting changes in there and they don't know what is the supposed way of keeping one's fork up-to-date. Read '''Keeping your fork up to date''' and find out! | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Publishing your Contributions == | ||

| + | <div style="float:right;width:400px;margin:30px;border:solid1px;"> | ||

| + | [[Image:Update distribution.png]]<br> | ||

| + | Updates are pushed and pulled between the various distributed repositories until they are finally distributed to every repository. (1) The contributor pushes his new commits to his public github fork and notifies the maintainer. (2) The maintainer pulls the commits into his private repository and resolves any (remaining) merge conflicts. (3) The maintainer publishes the change set to the public main repository. (4) All other contributors pull the change set into their code bases and base their further work on the new history. | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | OK, so now you have a couple of commits that you would like to contribute to the main repository? Better double check first if everything is fine because errors are most easily fixed in yet unpublished changes! | ||

| + | * Check if the code is compiling. If you committed only a part of your changes, stash away the rest and check. | ||

| + | * Check the test suite if your changes might have broken some tests | ||

| + | * If your change is based on a relatively old state of the main repository then you should probably bring your repository up-to-date first to see if the change is not creating any merge conflicts. See '''Keeping your fork up-to-date'''. | ||

| + | |||

| + | If everything is ok, publish the commits to your public github repository. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{code|git push origin master}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | When you cloned your local repo from github ''origin'' has already been set to ''git@github.com:YOURNAME/GitSharp.git''. If it is not set for some reason, do it like this: | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{code|git remote add origin git@github.com:YOURNAME/GitSharp.git}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Now that your commit is published, it doesn't mean that it has already been merged into the main repository. You should issue a merge request to one of the maintainers. They will pull your commits. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Please keep in mind, that there are many contributors and that the maintainers may miss that something changed in your fork or forget to merge in your commits. Remind them if they forgot. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | ;Publish Early and Often | ||

| + | The longer your change is not added to the main line, the higher is the potential for merge conflicts to arise because others may have fixed the same bug (not knowing that you already fixed it) or touched the same code for some other reasons. So push early and often, but push only if you are sure the changes compile and are working. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Keeping Your Fork Up-To-Date == | ||

| + | As your fork grows older, many other's contributions will have been merged into the main repository and your fork will slowly become more and more out-of-date. Again, be warned, the github Fork Queue is '''not''' the right tool for keeping fork's up to date. | ||

| + | |||

| + | You need to add the main repository to the list of your remotes. In this case we name the upstream repo after its current maintainer (henon). | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{code|git remote add henon git://github.com/henon/GitSharp.git}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Make sure your repository is clean (no uncommitted changes) and is currently on the master branch. If not, commit or stash any changes and switch to the master: | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{code|git checkout master}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Then you can pull all the new commits from the main line: | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{code|git pull henon master}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Remember, pull is a combination of the commands fetch and merge, so there may be merge conflicts to be manually resolved. The most confortable way to resolve conflicts is to use TortoiseGit's '''edit conflicts''' tool. | ||

| + | |||

| + | If you need to integrate with another developer but his commits have not yet been merged upstream just merge his branch directly. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Resolving Merge Conflicts === | ||

| + | If you are expecting conflicts it is wise to remember the hash value of your current head (i.e. write the first 8 digits of the hash on a piece of paper). To get it fire up gitk which is very convenient for browsing through the history or type | ||

| + | {{code|git show HEAD}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | If you want to undo the merge you can just go back by resetting hard to that hash as described in '''Something Went Wrong'''. If you are getting many conflicts it means you should have merged your branch with the main line more often. To resolve the conflicts use TortoiseGit, start the commit-Dialog, right click on the red files and choose "Edit conflicts". After editing the conflicting lines (marked red) click on the "Resolved"-Button. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Important: After you resolved all conflicts '''don't forget to commit''' and push. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === An Alternative for Github's Network Graph === | ||

| + | The network graph on github is a very handy tool (for both developers and maintainers) to see who has committed what to any fork recently. But unfortunately sometimes the graph has errors or you just need to wait hours for it. In this case you can do something else. Add the public clone urls of all relevant forks to your remote configuration as described above (using git remote add). Then you can download their commits without merging them: | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{code|git remote update}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | This fetches all commits of your remotes. Then launch gitk which is packaged with msysgit to see all your and other's branches you just downloaded. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{code|gitk --all}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | It provides the same information as the github network tree but is formatted differently. Anyway, it is the fastest way of getting a decent graph based visualization of the actual happenings of the project. Based on this overview you can better decide what to merge or not. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Non-linear coding: Working on multiple Topics == | ||

| + | |||

| + | TODO: describe working with topic branches | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Something Went Wrong == | ||

| + | '''Don't panic!''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Git lets you correct your errors! Depending on the publication status of your erranous commits it may be more or less efficient or easy. Easiest to fix errors are in unpublished commits. Even in your public fork you may correct the history of changes that are not yet merged into the main repository but it may take some time. Commits that have already been applied to the main line and thus are possibly already distributed over many contributor's private repositories errors can only be fixed by making new commits that revert the erraneus commit's changes but not by fixing the commit object directly. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Correcting errors in private unpublished commits === | ||

| + | In your private repository you are god. You can completely rewrite the history, but you shouldn't touch commits that have already been published and merged into the main repository. Otherwise you will suffer heavily next time you pull ;) or you cause others a lot of trouble when theiy want to pull from you. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Exemplary errors and fixes are: | ||

| + | * Forgot something in the last commit --> Amend | ||

| + | * Commited too much, like to split up into multiple commits --> Soft Reset | ||

| + | * Things went so wrong that you want to throw some commits away --> Hard Reset | ||

| + | |||

| + | Note: Before you play god, be careful! If you rewrite history which has already been pushed remote then you need to force overwriting the remote history or you won't be able to push again. See '''correcting errors in your public repo'''. If the commits you want to discard have already been propagated into other's repositories then you will probably cause a lot of trouble! | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | ;Amending last commit: | ||

| + | To edit the last commit use TortoiseGit, it is good at amending! On the command line it would be | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{code|git commit --amend}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ;Soft Reset: | ||

| + | A soft reset rewinds the HEAD back in history without discarding changes. Every change of a commit that has been reset softly can be committed again in order to rewrite the history differently. Identify the COMMITHASH right before things went wrong and type | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{code|git reset COMMITHASH}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ;Hard Reset: | ||

| + | A hard reset rewinds the HEAD back in history and discards any changes of the resetted commits. Identify the COMMITHASH right before things went wrong and type | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{code|git reset --hard COMMITHASH}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | So as you see, there are lots of possibilities to fix errors in local unpublished changes. Cool, isn't it? | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Correcting errors in your public remote repository === | ||

| + | Yes, git can do that too. But beware, as you can guess, much trouble can be caused by rewriting history that others have already based their work on. Only do this, if you are sure that no one has yet pulled the commits you want to change. | ||

| + | |||

| + | First of all, fix your local repository as described in the previous section. After that you can force your public repository to the new revision history. If the public repository is configured to allow forced pushes then simply do: | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{code|git push -f origin master}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | If the remote repository rejects a forced push there is still a trick, but it might take a little longer for big repositories (so beware): | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{code|git push origin :master<br> | ||

| + | git push origin master}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | To understand what's happening here you should know that push allows to push from one branch to the other with the following notation local_branch:remote_branch. A normal ''git push origin master'' is a shortcut for ''git push origin master:master''. If you leave the local branch blank it will delete the remote branch. The second push will then recreate it and transport your complete rewritten revision history to the remote repository. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Correcting errors that are already merged upstream === | ||

| + | You can correct errors that made it into the main repository only by creating a new commit that reverts the changes by the erranous commit. On the command line it is as easy as | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{code|git revert COMMITHASH}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Please do not confuse ''git revert'' with subversion's ''revert'' or TortoiseGit's ''revert'' which is actually a reset in git terminology. | ||

| - | + | == Further Reading == | |

| + | * [http://www-cs-students.stanford.edu/~blynn/gitmagic/ Git Magic]. A very good introduction to git | ||

| + | * [http://cheat.errtheblog.com/s/git Cheat Git]. A comprehensive compilation of examples. | ||

| + | * [http://progit.org/book/ Pro Git]. Open source book about git. | ||

| + | * [http://www.scribd.com/doc/6377254/Git-from-the-bottom-up-by-John-Wiegley Git from the bottom up] by John Wiegley (PDF) | ||

| - | + | == Contact the Autor == | |

| + | To contact me, drop me a mail to the following address: meinrad.recheis@gmail.com | ||

Latest revision as of 10:24, 28 April 2012

Typical distributed setup of git repositories for collaboration on a github hosted project. The dots are repositories, the lines between them indicate that one repository has been cloned from another. The forks are initially created by cloning from the main repository and the private repos are clones from the public ones on github.

Collaboration on Github is not complicated but also not intuitively clear for beginners because not all parts of the workflow are incorporated into the Github user interface. This description describes the structure of collaboration between the contributors and the maintainers of a project that is hosted on github. For every step in the workflow the respective git commands are given for reference.

The example

This description uses the project GitSharp as example. Git# is the CSharp implementation for Windows and Mono.

The main repository also called the upstream branch is henon/GitSharp. The maintainers of this repository are responsible of merging in contributor's commits.

Contributor's Workflow

Getting Started

- Overview

- Fork

- Install tools like git itself (if not yet done)

- Clone

- Start coding ;)

- Commit early and commit often

- Ignore the Github Fork Queue

- Fork

Say you want to start contributing to a project on github. The first thing to do is to fork it on github. Forking is the preferred way of collaboration on github and it works quite well with git. Just follow the instructions on github. Now you should have your own public repository which contains exactly the same history as the main repository at the time you forked. You will later push your contributions into this repository and the maintainers of the main repository will pull your commits into the main branch.

- Install Git Tools (Windows)

- msysgit: make sure it is configured to use OpenSSH and that automatic line ending conversion is turned off during installation. You can use the msysgit-bash to use git from the command line.

- TortoiseGit: is not yet completely done but is already very usable for things like adding files, committing changes or resolving merge conflicts.

If you prefer other tools let me know what they are especially good for. I will include them in this document.

- Clone

By cloning your fork on github you create your private local repository on your box. You will mostly work with it and only publish changes to github when you feel they should be merged into the main repository.

git clone git@github.com:YOURNAME/GitSharp.git

Of course this only works if you managed to create an SSH key and successfully uploaded it to github. I will not go into details on this, because it is already documented very well on github itself. If you experienced any problems with this step tell me and I will put them here.

Now you got a git repository called GitSharp and are ready to start coding!

- Start Coding!

Coding with git backing you up is really cool because you can so easily work on multiple topics at the same time efficiently. I'll give you a simple example:

You got a cool new idea and start working on it. You modify some files. You are not yet done, and your changes not even compile yet. Meanwhile you read on the mailing list that someone has got a problem with a specific test case and cannot get it to work. You would like to help because you know things like these very well and you are the type of human who cannot resist doing good :D. But what to do with your non finished code? Stash it away!

git stash topic_XY

Git saves away your changes and your working copy is clean and compiles again. Now you fix the bug for your friend, commit the fix and publish it to your fork where others can access it. We talk about publishing contributions later more thoroughly. Now you can apply your saved away changes and continue working on it:

git stash apply topic_XY

This is only a small example of how git supports non-linear development in a great way. Read more on it in the docs linked under Further Reading.

- Commit Early and Commit Often

When you are doing much coding, maybe refactoring a large code base or commenting source code you should keep in mind that other's are also modifying the same code base and that conflicts may arise. In order to make it easier for you and the others to resolve such conflicts on a per-commit basis try to commit as often as possible and commit only small changes. Provide a meaningful message for every commit so that anyone reviewing the commit later knows from reading the message what the commit changes.

For the beginner I'd suggest seperating unrelated changes on a file per file basis, although git allows much more fine-grained control over the changes to commit. Committing a selection of files can most conveniently be done in TortoiseGit. You can select the files that you want to commit, compare against the local repository what changes you made and comment your changes in the commit message. Of course it can also be done on the command line interface First stage all changes you want to commit by using git add.

git add FILE1 [FILE2] ...

If you don't want to stage all changes in a file but only certain hunks, use the interactive mode

git add -i

Now check if everything has been added or if you missed something

git status

Committing on the command line (btw, never forget -a):

git commit -a -m"The commit message"

Always keep in mind that errors happen all the time. If it is later necessary to revert certain changes because they broke something else's code then reverting a small commit is easy and not much of a problem. If the change to be reverted is mixed up with lots of other changes the reverting of such a commit will be a painful night mare. If you have already committed a "monster commit" to your local repo then don't worry. With git it is no problem to rewrite the commit history. Read about that later.

Here are some examples of commit messages for some unrelated changes that should not be committed in the same commit object would be:

- Converted all line endings to CRLF in the complete code base

- Documented the methods of Class XY

- Fixed TestcaseXY so that it now passes

- Added a new Feature to the UI, description follows: ...

- Ignore the Github Fork Queue

It's evil! The fork queue is a tool for maintainers who like to pick single commits from contributors but don't wish to merge in their whole branch. If you play around with the fork queue you will corrupt your fork (it can be fixed though, read Something went wrong). Many newbies on github feel like they should do something with the fork queue because there are a lot of possibly conflicting changes in there and they don't know what is the supposed way of keeping one's fork up-to-date. Read Keeping your fork up to date and find out!

Publishing your Contributions

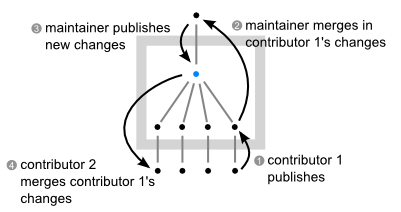

Updates are pushed and pulled between the various distributed repositories until they are finally distributed to every repository. (1) The contributor pushes his new commits to his public github fork and notifies the maintainer. (2) The maintainer pulls the commits into his private repository and resolves any (remaining) merge conflicts. (3) The maintainer publishes the change set to the public main repository. (4) All other contributors pull the change set into their code bases and base their further work on the new history.

OK, so now you have a couple of commits that you would like to contribute to the main repository? Better double check first if everything is fine because errors are most easily fixed in yet unpublished changes!

- Check if the code is compiling. If you committed only a part of your changes, stash away the rest and check.

- Check the test suite if your changes might have broken some tests

- If your change is based on a relatively old state of the main repository then you should probably bring your repository up-to-date first to see if the change is not creating any merge conflicts. See Keeping your fork up-to-date.

If everything is ok, publish the commits to your public github repository.

git push origin master

When you cloned your local repo from github origin has already been set to git@github.com:YOURNAME/GitSharp.git. If it is not set for some reason, do it like this:

git remote add origin git@github.com:YOURNAME/GitSharp.git

Now that your commit is published, it doesn't mean that it has already been merged into the main repository. You should issue a merge request to one of the maintainers. They will pull your commits.

Please keep in mind, that there are many contributors and that the maintainers may miss that something changed in your fork or forget to merge in your commits. Remind them if they forgot.

- Publish Early and Often

The longer your change is not added to the main line, the higher is the potential for merge conflicts to arise because others may have fixed the same bug (not knowing that you already fixed it) or touched the same code for some other reasons. So push early and often, but push only if you are sure the changes compile and are working.

Keeping Your Fork Up-To-Date

As your fork grows older, many other's contributions will have been merged into the main repository and your fork will slowly become more and more out-of-date. Again, be warned, the github Fork Queue is not the right tool for keeping fork's up to date.

You need to add the main repository to the list of your remotes. In this case we name the upstream repo after its current maintainer (henon).

git remote add henon git://github.com/henon/GitSharp.git

Make sure your repository is clean (no uncommitted changes) and is currently on the master branch. If not, commit or stash any changes and switch to the master:

git checkout master

Then you can pull all the new commits from the main line:

git pull henon master

Remember, pull is a combination of the commands fetch and merge, so there may be merge conflicts to be manually resolved. The most confortable way to resolve conflicts is to use TortoiseGit's edit conflicts tool.

If you need to integrate with another developer but his commits have not yet been merged upstream just merge his branch directly.

Resolving Merge Conflicts

If you are expecting conflicts it is wise to remember the hash value of your current head (i.e. write the first 8 digits of the hash on a piece of paper). To get it fire up gitk which is very convenient for browsing through the history or type

git show HEAD

If you want to undo the merge you can just go back by resetting hard to that hash as described in Something Went Wrong. If you are getting many conflicts it means you should have merged your branch with the main line more often. To resolve the conflicts use TortoiseGit, start the commit-Dialog, right click on the red files and choose "Edit conflicts". After editing the conflicting lines (marked red) click on the "Resolved"-Button.

Important: After you resolved all conflicts don't forget to commit and push.

An Alternative for Github's Network Graph

The network graph on github is a very handy tool (for both developers and maintainers) to see who has committed what to any fork recently. But unfortunately sometimes the graph has errors or you just need to wait hours for it. In this case you can do something else. Add the public clone urls of all relevant forks to your remote configuration as described above (using git remote add). Then you can download their commits without merging them:

git remote update

This fetches all commits of your remotes. Then launch gitk which is packaged with msysgit to see all your and other's branches you just downloaded.

gitk --all

It provides the same information as the github network tree but is formatted differently. Anyway, it is the fastest way of getting a decent graph based visualization of the actual happenings of the project. Based on this overview you can better decide what to merge or not.

Non-linear coding: Working on multiple Topics

TODO: describe working with topic branches

Something Went Wrong

Don't panic!

Git lets you correct your errors! Depending on the publication status of your erranous commits it may be more or less efficient or easy. Easiest to fix errors are in unpublished commits. Even in your public fork you may correct the history of changes that are not yet merged into the main repository but it may take some time. Commits that have already been applied to the main line and thus are possibly already distributed over many contributor's private repositories errors can only be fixed by making new commits that revert the erraneus commit's changes but not by fixing the commit object directly.

Correcting errors in private unpublished commits

In your private repository you are god. You can completely rewrite the history, but you shouldn't touch commits that have already been published and merged into the main repository. Otherwise you will suffer heavily next time you pull ;) or you cause others a lot of trouble when theiy want to pull from you.

Exemplary errors and fixes are:

- Forgot something in the last commit --> Amend

- Commited too much, like to split up into multiple commits --> Soft Reset

- Things went so wrong that you want to throw some commits away --> Hard Reset

Note: Before you play god, be careful! If you rewrite history which has already been pushed remote then you need to force overwriting the remote history or you won't be able to push again. See correcting errors in your public repo. If the commits you want to discard have already been propagated into other's repositories then you will probably cause a lot of trouble!

- Amending last commit

To edit the last commit use TortoiseGit, it is good at amending! On the command line it would be

git commit --amend

- Soft Reset

A soft reset rewinds the HEAD back in history without discarding changes. Every change of a commit that has been reset softly can be committed again in order to rewrite the history differently. Identify the COMMITHASH right before things went wrong and type

git reset COMMITHASH

- Hard Reset

A hard reset rewinds the HEAD back in history and discards any changes of the resetted commits. Identify the COMMITHASH right before things went wrong and type

git reset --hard COMMITHASH

So as you see, there are lots of possibilities to fix errors in local unpublished changes. Cool, isn't it?

Correcting errors in your public remote repository

Yes, git can do that too. But beware, as you can guess, much trouble can be caused by rewriting history that others have already based their work on. Only do this, if you are sure that no one has yet pulled the commits you want to change.

First of all, fix your local repository as described in the previous section. After that you can force your public repository to the new revision history. If the public repository is configured to allow forced pushes then simply do:

git push -f origin master

If the remote repository rejects a forced push there is still a trick, but it might take a little longer for big repositories (so beware):

git push origin :master

git push origin master

To understand what's happening here you should know that push allows to push from one branch to the other with the following notation local_branch:remote_branch. A normal git push origin master is a shortcut for git push origin master:master. If you leave the local branch blank it will delete the remote branch. The second push will then recreate it and transport your complete rewritten revision history to the remote repository.

Correcting errors that are already merged upstream

You can correct errors that made it into the main repository only by creating a new commit that reverts the changes by the erranous commit. On the command line it is as easy as

git revert COMMITHASH

Please do not confuse git revert with subversion's revert or TortoiseGit's revert which is actually a reset in git terminology.

Further Reading

- Git Magic. A very good introduction to git

- Cheat Git. A comprehensive compilation of examples.

- Pro Git. Open source book about git.

- Git from the bottom up by John Wiegley (PDF)

Contact the Autor

To contact me, drop me a mail to the following address: meinrad.recheis@gmail.com